Knowledge Extraction for Literature Review

Abstract

Researchers in all domains need to keep abreast with recent scientific advances. Finding relevant publications and reviewing them is a labor-intensive task that lacks efficient automatic tools to support it. Current tools are limited to standard keyword-based search systems that return potentially relevant documents and then leave the user with a monumental task of sifting through them.In this paper, we present a semantic-driven system to automatically extract the most important knowledge from a publication and reduces the effort required for the literature review. The system extracts key findings from biomedical papers in PubMed, populates a predefined template and displays it. This allows the user to get the key ideas of the content even before opening or downloading the publication.Keywords

Literature review; knowledge extraction; semantic relation

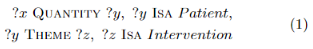

1. INTRODUCTION Researchers in many domains have the need to quickly grasp the big picture presented in current publications in various topic. Reviewing document repositories to find relevant publications and skim them for appropriateness is time consuming and labor-intensive process. There are recommendations [3] from experienced researchers to students on how to undertake the task in a more optimal way, based on heuristics on what sections of the paper should be scanned through first. In biomedical domain, the systematic review process goes from thousands of publications found by key-word-based search to tens that are reviewed in-depth, and the process of filtering remains manual.There have been a few efforts targeted at providing the users with some overview information regarding the nature and content of the publication of interest. In general purpose information retrieval systems, the current approach is to provide snippets or citations to the user so that the relevance of the document can be assessed before reading the whole document. Another approach includes associating tags with the documents. However, these snippets and tags do not provide a coherent picture. MEDLINE, a large bibliographic database in biomedical domain, contains metadata associated with each citation, extracted in a partially auto-mated way [2]. However, this metadata omits some important information such as dosage, explicit relations between intervention and outcome, etc.Our approach combines the ideas of snippets and key-word annotations and populates predefined templates that are displayed with the publications. The predefined template is based on the PICO [4] model and represents the key findings presented in the paper along with its study settings. These hints about the content of the paper allow researchers to gain vital knowledge while saving time required to sift through large number of articles.2. KNOWLEDGE EXTRACTIONThe population of the template with key information is based on deep semantic parsing and knowledge extraction. Figure 1 shows the semantic representation of a sentence from a sample paper [6] and the populated template fragment. The system extracts concepts of interest and high-level relations. Such representation of all sentences with information of the document’s structure is used to populate the template. The template slots include problem description (disease, condition, etc), interventions (medical procedures, diagnosis tests, medication), and outcomes (new values for vital sign measures, improvement, adverse effects, etc). An important part of the template is study design that includes the size of the trial group, and patient sociodemographic characteristics. Both concepts and relations are indexed in Apache Solr with concepts being indexed as tokens and relations being indexed as a separate Solr field.2.1 CONCEPT EXTRACTIONThe first step in the knowledge extraction process is concept extraction. This process is driven by ontologies and lexical patterns. In biomedical domain, the system benefits from existing medical ontologies: MeSH, SNOMED and UMLS Metathesaurus. Our hybrid approach to named entity recognition makes use of machine learning classifiers, cascade of finite state automata, and lexicons to label more than 80 types of named entities. In addition to key medical categories like disease, vital sign, medication, procedure, etc, the module extracts their attributes: quantity, dosage, severity, time course, onset, alleviating and aggravating factors, as well as negative findings and family history.Permission to make digital or hard copies of part or all of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. Copyrights for third-party components of this work must be honored. For all other uses, contact the owner/author(s).

JCDL ’16, June 19-23, 2016, Newark, NJ, USA.

© 2016 Copyright held by the owner/author(s).

ACM ISBN 978-1-4503-4229-2/16/06.

DOI:\doi{http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2910896.2925441}

Figure 1: Semantic representation of a sentence from a sample paper and the resulting template fragment for the paper [6].

2.2 Basic Semantic ParsingThe next stage in our automatic template population process is the extraction of basic semantic relations. The semantic parser extracts binary relations between concepts and content words in the sentence. We use 26 predefined relation types, following [5]. The relations are not limited by verb arguments, but include such relations as QUANTITY, PROPERTY, POSESSION and others to represent semantic connectivity between all content words. These relations follow syntactic structures closely and can be automatically extracted in a robust manner. We use a hybrid approach to semantic parsing: machine learning classifiers for argument pairs identified using syntactic patterns and filtered using ontology-based restrictions on candidate arguments. Finally, the overall semantic structure is analyzed to resolve the conflicts. For example, in Figure 1, the following basic semantic relations are extracted: VALUE(resistant, hypertension), THEME(subjects, screened) and THEME(antihypertensiveagents, use).2.3 Semantic Calculus: Custom Relation ExtractionWhile basic semantic relations provide a robust representation of the semantic structure, they are of no interest to the end users and cannot be used for knowledge extraction directly. However, basic relations provide a foundation for extraction of domain-specific relations via Semantic Calculus [1]. The Semantic Calculus defines how and under what conditions a chain of relations can be combined into a high-level custom relation. In a trivial case, Semantic Calculus rules relabel one basic relation into a more specific one.For example rule POSESSION(c1, c2) & ISA (c1, disease)&ISA (c2, organism)⇒HAS DISEASE (c1, c2) relabels POSESSION(diabetes, subjects) into HASDISEASE. Another group of rules extracts the same 26 relation types via combination of two basic relations. This is used to propagate Location and Time relations and make the semantic structure more tight [1]. The most complex rules combine relation chains into high-level domain-specific relations. For example, relation HAS SIGN in Figure 1 is not expressed directly, but can be extracted with axioms: blood pressure is a property of hypertension, and hypertension is related to subjects.2.4 Template PopulationThe extracted relations are saved into an RDF store and then queried to populate the templates. Each template slot is filled via several SPARQL queries. For example to extract the group size, we are looking for x with the following query: The second line of this query is needed to make sure that the quantity is for the whole study group and not for a subset with a particular outcome. The output for the query is post-processed to avoid duplicates. Finally, the output is normalized: phrases head words are converted to lemmas and cardinals are replaced by their digit representation.

3. CONCLUSIONWe tested our system on articles targeting treatment efficiency studies in the PubMed publication repository. We processed more than 8 million article abstracts in PubMed for the years from 2005 to 2015. The system can process around 100,000 articles per day per CPU core, and automatically extract knowledge to populate the predefined document template for each article. The automatically populated templates present key information from the paper which allows users to decide whether the paper is worth reading without reviewing it manually. This approach can be applied to other domains to ease the burden of monitoring journals and conference proceedings.4. REFERENCES[1] E. Blanco and D. Moldovan. Composition of semantic relations: Theoretical framework and case study. ACM Trans. Speech Lang. Process., 10(4):17:1–17:36, Jan.2014.[2] K. B. Cohen and D. Demner-Fushman. Biomedical Natural Language Processing. John Benjamin Publishing Company, 2014.[3] J. Eisner. How to read a technical paper. https://www.cs.jhu.edu/ ̃jason/advice/how-to-read-a-paper.html.[4] X. Huang, J. Lin, and D. Demner-Fushman. Evaluation of PICO as a knowledge representation for clinical questions. In AMIA Annu Symp Proc., pages 359–363,2006.[5] D. Moldovan and E. Blanco. Polaris: Lymba’s semantic parser. In Proceedings of LREC-2012, pages 66–72,2012.[6] G. E. Umpierrez, P. Cantey, D. Smiley, A. Palacio, D. Temponi, K. Luster, and A. Chapman. Primary aldosteronism in diabetic subjects hypertension. Diabetes Care, 30(7): 1699–1703, July 2007.