Inducing Ontologies from Folksonomies using

Natural Language Understanding

Abstract

Folksonomies are unsystematic, unsophisticated collections of keywords associated by social bookmarking users to web content and, despite their inconsistency problems (typographical errors, spelling variations), their popularity is increasing among Web 2.0 application developers. In this paper, we, not only eliminate folksonomic irregularities, but structure the folksonomy by exploiting the tags, their social bookmarking associations and, more importantly, the content of labeled documents. We derive the semantics of each tag and expose the underlying semantic structure of the folksonomy, thus, enabling a number of information discovery and ontology-based reasoning applications.

1. INTRODUCTION

Social bookmarking has rapidly emerged as a tool that allows users to associate subjective descriptions to web pages. It helps its users organize and recall information of interest. Moreover, by sharing their bookmarks, users are able to identify other users with common interests as well as other resources of interest. Examples of popular social bookmarking sites include Delicious(www.delicious.com), Flickr (www.flickr.com), and BibSonomy (www.bisonomy.com).

The labels used within social bookmarking set-tings generate a folksonomy (folk + taxonomy). This flat lexicon with all user tags contains inconsistencies: the users’ uncontrolled vocabulary includes different types of variations and ambiguity, e.g., case sensitivity of tags, use of space or punctuation as delimiters, both singular and plural forms, same tag applied in different context, and synonymy of concepts (Golder and Huberman, 2005). Adam Mathes1 notes The sheer multiplicity of terms and vocabularies may overwhelm the content with noisy metadata that is not useful or relevant to a user.

Advanced linguistic processing of tags results in a better organization and management of folksonomies as well as improved sharing of resources. By explicitly capturing and representing tag semantics in a more formal taxonomy (an ontology), the information structure of user tags is revealed, thus, facilitating machine understanding of user interests. In this article, we describe our efforts to derive ontological structures from folksonomies using natural language processing (NLP) and automatic ontology generation technologies.

1.1 Overview of Technical Approach

Because folksonomies are collections of tags, our initial efforts in designing a formal representation of folksonomies focused on the tags and their representation. For each tag, we derived a rich semantic representation that captures its concepts and any semantic relations that link them. Thus, each tag becomes a rich semantic graph that can be easily exploited during the process of organizing the tags. For example, the tag americanhistory is represented asAmerican|JJ|←TOPIC←−history|N N|2.

We note that each concept part of a tag representation is linked to its corresponding WordNet synset(American|JJ|1is part of synset id 2785615).These links enable the system to identify synonyms((word, sense) pairs that denote the same WordNetconcept). Moreover, metadata, including language and bookmarking information and frequency statistics, accompany each tag.

At the folksonomy level, semantic relations, such as ISA, PARTWHOLE (PW), or SYNONYMY(SYN), link the tags, inducing the folksonomy’s rich semantic structure. Thus, folksonomies become rich semantic graphs whose links are the semantic relations connecting the folksonomic tags, which con-stitute the nodes of the representation.

Figure 1: System architecture

In order to derive rich semantic representations of tags, we developed mechanisms that normalize the lexical, syntactic, and semantic variations present in the folksonomic data. For this purpose, we exploited not only a tag’s textual information, but also its associations with other tags and documents as created by the social bookmarking users. Once we captured each tag’s meaning in a rich semantic representation, we used a series of classification steps that produce numerous tag-tag relationships, which complete the folksonomic ontology. SYN, ISA,PW, SIMILARITY (SIM), DOMAIN (DOM), AT-TRIBUTE (ATR), and other relations between tags expose the folksonomy’s ontological organization. Figure 1 displays our system’s architecture.

1.2 Experimental Data

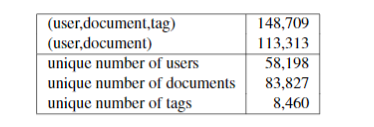

For evaluation purposes, we collected real-world social bookmarking data from Delicious (Table 1). 10% of the tags (randomly selected) were used to score each processing step’s performance. Using Lymba’s suite of NLP tools, we processed cached versions of the bookmarked documents focusing on English textual documents whose content will be used to capture each tag’s semantics (Section 2).

Table 1: Statistics of experimental dataset

2. Capturing Tag Semantics

We broke down the tag understanding process into eight different linguistic processing steps. Each stage uses three sources of information that provide complementary information to our system: (1)the tag space: the text of each tag is used to derive information about the tag, (2)the social bookmarking data: tag associations augment and refine the initial understanding of a given tag, and (3)the content of textual documents: situating a tag within the larger semantic context of the documents it was assigned to enhances the existing understanding of a given tag.

2.1 Lexical Understanding of Tags

During the tag language identification step, each tag text was matched against various dictionaries. For definite match cases, the tag language was identified. If two or more languages had similar matching scores, the decision was made based on the language of the documents labeled with it. We note that “universal” words, such as the numbers and most technical terms and names (e.g., linux, css, google),were tagged as belonging to the English language.

By verifying whether a tag belongs to a certain language vocabulary, we also determine whether it is a single token. The tag tokenization step is important because many social bookmarking tools use space as a tag separator for user input (american-history is a valid Delicious tag) If not found as part of a language vocabulary, then (1) the tag contains two or more words “glued” together, which should be tokenized for a correct understanding of

the tag, (2) the single token tag was misspelled and should be corrected, or (3) a combination of (1) and(2). Typographical errors and spelling variations are abundant in folksonomies, requiring a mandatory spelling correction step. Thus, for each unmatched tag, correctly spelled candidates include valid vocabulary concepts that minimize the edit distance to our input tag. Furthermore, we break the tag into multiple vocabulary items. Generated candidates are scored based on their presence within document content labeled with this tag. If they are part of the folksonomy and share documents or users with the analyzed tag (co-occurring tags), their scores are boosted. For further processing, we use the highest scoring variation of the tag text.

In order to restore the capitalization of tags that may denote proper names, we compare each tag text with the content of its corresponding documents. Documents include the correct spelling and capitalization information for a tag. The capitalization of a tag plays an important role in the process of identifying named entities.

2.2 Syntactic Understanding of Tags

For the part-of-speech tagging step, preference is given to the NOUN part-of-speech for single word tags, which cannot be tagged within context. Ambiguities are resolved by selecting the part-of-speech marked within the content of the tag’s documents.

For tags with multiple tokens, the syntactic parsing step identifies the type of the tag phrase, its syntactic head as well as any grammatical dependencies between its constituents. This information is needed by Lymba’s semantic parser as well as the ontology generation procedure (Section 3).

2.3 Semantic Understanding of Tags

First, we disambiguate abbreviations that either form or are part of tags using Lymba’s abbreviation dictionary (118,055 abbreviations, 25% with multiple definitions). We build lexical chains of WordNet synset-synset relations between tag-describing concepts (co-occurring tags and associated document content) and candidate definitions. Because short chains indicate strong semantic similarity, we identify the correct interpretation for an abbreviation.

The semantic disambiguation process continues with the sense identification step which assigns each tag or tag concept its

corresponding WordNet sense number. The word sense disambiguation process exploits the linguistic context of the analyzed word, which, in the case of folksonomic tags, is provided by their corresponding documents and the set of co-occurring tags. We note that we use Word-Net as our sense inventory. For non-WordNet concepts, Lymba’s named entity recognizer associates named entity classes to tags. These can be derived from the content of the tag’s documents, or based on the grammar rules and lexicons the module uses (no context is needed for certain named entity classes such as date, number, money, etc).

For multi-word tags, a semantic parsing step is required. We use Lymba’s semantic parser to discover relations that connect the tag’s constituents. Using a combination of semantic rules and machine learning classifiers, we identify 35 semantic relations, including ISA, PW, TEMPORAL (TMP), IN-STRUMENT (INS), and AGENT (AGT).

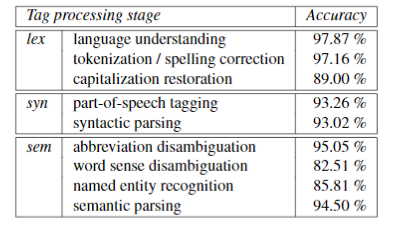

2.4 Tag Understanding Evaluation

In Table 2, we summarize the performance of the system’s tag understanding stages. Most errors occur when tags cannot be identified within their corresponding documents. Propagation errors from the capitalization restoration step account for future mistakes made during the part-of-speech tagging and named entity recognition stages.

Table 2: Accuracy of individual tag processing stages

3 Deriving the Folksonomy’s Structure from Tag Semantics

EQUALITY (EQ) relations link tags semantically normalized to the same form. Thus, EQ relations are created between tags with the same lemma, part-of-speech, and sense number (e.g, EQ(activity, activities), EQ(after-effects, AfterEffects), and EQ(opinion, Opnion)).

SYN relations link tags with identical synset ids, e.g. Archeology and Archaeology, OS and operating.system. For non-WordNet concepts, we use the named entity and abbreviation information, e.g. SYN(LA, losangeles), SYN(nyt, nytimes). We also create SYN relations between multi-word tags that have synonymous constituents linked by the same semantic relations.

Existing WordNet relations that link two folksonomic tags are also added to our ontology, e.g. ISA(vegan, vegetarian), PW(Businesses, markets), ENTAIL(proofreading, +read), and SIM(important, general).

Furthermore, we build lexical chains of size two between tags (tag1→rel1→synset→rel2−→tag2). We use Lymba’s semantic calculus rules (Tatu and Moldovan, 2006), which derive new semantic relations by combining two existing relationships, to add new tag-tag relations to our ontology, e.g., ISA(integration, events,) derived from ISA(integration, group action/NN/1) and ISA(groupaction/NN/1, events,); PW(lobby, ho-tels) derived from PW(lobby, building/NN/1) and ISA(hotels, building/NN/1).

Additional ISA relations are created betweennamed entity tags and WordNet synsets that de-scribe their corresponding named entity class,e.g., ISA(OracleCorporation, organization), ISA(davidfosterwallace, person).

For complex tags of the form mod head, where head ∈ folksonomy and REL(mod, head), we add ISA(mod head, head) relations, e.g. ISA(book-cover, covers), ISA(theoryofmind, theory), and ISA(photoshoptutorials, tutorials,).

For complex tags of the form modi headi where there exists a semantic relation REL(modi, headi),(i=1,2), we add a new ISA relation between the tags if (1) ISA(mod1,mod2) and ISA(head1, head2), (2) ISA(mod1,mod2) and SYN(head1, head2), or (3) SYN(mod1, mod2) and ISA(head1, head2). Also, if SYN(mod1, mod2) and REL(head1, head2), where REL could be any semantic relation, then a newREL relation is added to the ontology. Examples include ISA(build-solar-panel, create-solar-panel), SIM(socialnetworks, socialweb) (based on the SIM(networks, web) which

was derived using Lymba’s semantic calculus rules - both nouns are derivations of the concept web/VB/1).

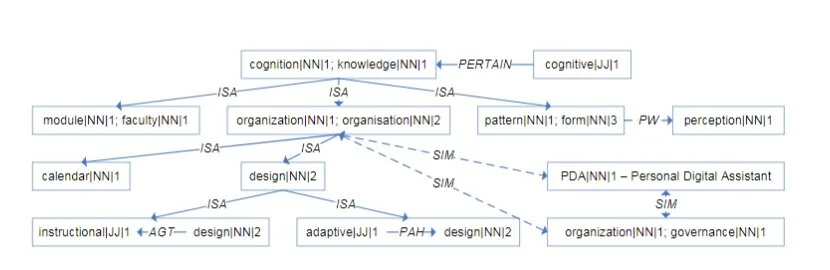

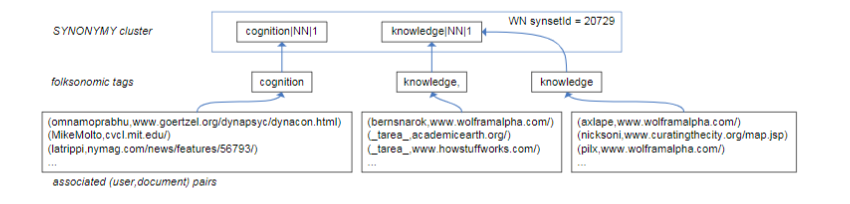

Sanity checks that ensure a consistent ontology structure, which can support applications involving the input folksonomy, include (1) identity and resolution of conflicts as well as (2) redundancy checks. We show a small portion from a generated ontology in Figure 2. Its nodes contain richer information not shown in Figure 2 (sample in Figure 3).

3.1 Relation Generation Evaluation

Given perfect input, the classification rules de-scribed above derive a highly-accurate set of tag-tag semantic connections. However, given the sense disambiguation errors, tags are placed into incorrect SYN clusters more than 17% of the time, affecting the relation generation process. The accuracy of this processing step is 80.30%, as measured on a randomly selected set with 20% of the total 5,439 relations (ISA - 3869, SIM - 601, PW - 429, etc.).

4 Conclusion

In this paper, we described a method that exposes the latent semantic structure of folksonomies, thus, eliminating their inconsistency problems and linking semantically related tags. The resulting structure is a rich graph with nodes that represent clusters of synonymous tags and labeled directed links that denote the semantic relations that connect the folksonomic tags. Projections of this graph, which include only relationships such as ISA and PW, reveal hierarchical organizations of the folksonomy which can be exploited by social web applications.

References

S. Golder and B.A. Huberman.2005.TheStructure of Collaborative Tagging Systems. Technical report, HP Labs. Available at http://www.hpl.hp.com/research/idl/papers/tags.Marta Tatu and Dan Moldovan. 2006. A Logic-based Semantic Approach to Recognizing Textual Entailment. In Proceedings of COLING/ACL 2006.

Figure 2: Sample portion of automatically induced folksonomic ontology

Figure 3: SYN cluster of normalized tags with social meta information