Automatic Discovery of Manner Relations and its Applications

ABSTRACT

This paper presents a method for the automatic discovery of MANNER relations from text. An extended definition of MANNER is proposed, including restrictions on the sorts of concepts that can be part of its domain and range. The connections with other relations and the lexico-syntactic patterns that encode MANNER are analyzed. A new feature set specialized on MANNER detection is depicted and justified. Experimental results show improvement over previous attempts to extract MANNER. Combinations of MANNER with other semantic relations are also discussed.

1. Introduction

Extracting semantic relations from text is an important step towards understanding the meaning of text. Many applications that use no semantics, or only shallow semantics, could benefit by having available more text semantics. Recently, there is a growing interest in text semantics (Marquez et al., 2008; Davidov and Rappoport, 2008).

An important semantic relation for many appli-cations is the MANNER relation. Broadly speaking, MANNER encodes the mode, style, way or fashion in which something is done or happened. For example, quick delivery encodes a MANNER relation, since quick is the manner in which the delivery happened.

An application of MANNER detection is Question Answering, where many how questions refer to this particular relation. Consider for example the question How did the President communicate his mes-

sage?, and the text Through his spokesman, Obama sent a strong message [. . . ]. To answer such questions, it is useful to identify first the MANNER relations in text

MANNER occurs frequently in text and it is expressed by a wide variety of lexico-syntactic patterns. For example, Prop Bank annotates8,037ARGM-MNRrelations (10.7%) out of 74,980adjunct-like arguments (ARGMs). There are verbs that state a particular way of doing something, e.g., to limp implicitly states a particular way of walking. Adverbial phrases and prepositional phrases are the most productive patterns, e.g., The nation’s industrial sector is now growing very slowly if at all and He started the company on his own. Consider the following example: The company said Mr. Stronach will personally direct the restructuring assisted by Manfred Gingl, [. . . ]1. There are two MANNER relations in this sentence: the under-lined chunks of text encode the way in which Mr. Stronach will direct the restructuring.

2. Previous Work

The extraction of semantic relations in general has caught the attention of several researchers. Approaches to detect semantic relations usually focus on particular lexical and syntactic patterns. There are both unsupervised (Davidov et al., 2007; Turney, 2006) and supervised approaches. The SemEval2007 Task 04 (Girju et al., 2007) aimed at relations between nominals. Work has been done on detecting relations within noun phrases (Nulty, 2007), named entities (Hirano et al., 2007), clauses (Sz-pakowicz et al., 1995) and syntax-based comma resolution (Srikumar et al., 2008).

There have been proposals to detect a particular relation, e.g.,CAUSE(Chang and Choi, 2006),INTENT(Tatu, 2005), PART-WHOLE(Girju et al., 2006) and IS-A(Hearst,1992).

MANNER is a frequent relation, but besides theoretical studies there is not much work on detecting it. Girju et al. (2003) propose a set of features to extract MANNER exclusively from adverbial phrases and report a precision of 64.44% and recall of 68.67%. MANNER is a semantic role, and all the works on the extraction of roles (Gildea and Jurafsky, 2002; Giuglea and Moschitti, 2006) extracts MANNER as well. However, these approaches treat MANNER as any other role and do not use any specific features for its detection. As we show in this paper, MANNER has its own unique characteristics and identifying them improves the extraction accuracy. The two most used semantic role annotation resources, FrameNet (Baker et al., 1998) and Prop-Bank (Palmer et al., 2005), include MANNER.

The main contributions of this paper are: (1) empirical study of MANNER and its semantics;(2) analysis of the differences with other relations;(3) lexico-syntactic patterns expressing MANNER;(4) a set of features specialized on the detection of MANNER; and (5) the way MANNER combines with other semantic relations.

3. The Semantics of MANNER Relation

Traditionally, a semantic relation is defined by stating the kind of connection linking two concepts. For example, MANNER is loosely defined by the PropBank annotation guidelines as manner adverbs specify how an action is performed [. . . ] manner should be used when an adverb be an answer toa question starting with ’how?’. We find this kind of definition weak and prone to confusion (Section3.2). Nonetheless, to the best of our knowledge, semantic relations have been mostly defined stating only a vague definition. Following (Helbig, 2005), we propose an ex-tended definition for semantic relations, including semantic restrictions for its domain and range.

These restrictions help deciding which relation holds between a given pair of concepts. A relation shall not hold between two concepts unless they be-long to its domain and range. These restrictions are based on theoretical and empirical grounds.

3.1 Manner Definition

Formally, MANNER is represented as MNR(x, y), and it should be read x is the manner in which y happened. In addition, DOMAIN(MNR) and RANGE(MNR) are the sets of sorts of concepts that can be part of the first and second argument.

RANGE(MNR), namely y, is restricted to situations, which are defined as anything that happens at a time and place. Situations include events and states and can be expressed by verbs or nouns, e.g., conference, race, mix and grow. DOMAIN(MNR), namely x, is restricted to qualities (ql),non temporal abstract objects (ntao)and states (st).Qualities represent characteristics that can be assigned to other concepts, such as slowly and abruptly. Non temporal abstract objects are intangible entities. They are somehow product of human reasoning and are not palpable. They do not encode periods or points of time, such as week, or yesterday. For example, odor, disease, and mile are ntao; book and car are not because they are tangible. Unlike events, states are situations that do not imply a change in the concepts involved. For example, standing there or holding hands are states; whereas walking to the park and pinching him are events. For more details about these semantic classes, refer to (Helbig, 2005).

These semantic restrictions on MANNER come after studying previous definitions and manual examination of hundreds of examples. Their use and benefits are described in Section 4.

3.2 MANNER and Other Semantic Relations

MANNER is close in meaning with several other relations, specifically INSTRUMENT, AT-LOCATION and AT-TIME.

Asking how does not identify MANNER in many cases. For example, given John broke the window[with a hammer], the question how did John break the window? can be answered by with the hammer, and yet the hammer is not the MANNER but the INSTRUMENT of the broke event.

Other relations that may be confused as MANNER include AT-LOCATION and AT-TIME, like in [The dog jumped]x [over the fence]y and [John used to go]x [regularly]y.

A way of solving this ambiguity is by prioritizing the semantic relations among the possible candidates for a given pair of concepts. For example, if both INSTRUMENT and MANNER are possible, the former is extracted. In a similar fashion, AT-LOCATION and AT-TIME could have higher priority than MANNER. This idea has one big disadvantage: the correct detection of MANNER relies on the detection of several other relations, a problem which has proven difficult and thus would unnecessarily introduce errors.

Using the proposed extended definition one may discard the false MANNER relations above. Hammer is not a quality, non temporal abstract objector state (hammers are palpable objects), so by definition a relation of the form MNR(the hammer, y) shall not hold. Similarly, fence and week do not fulfill the domain restriction, so MNR(over the fence, y) and MNR(every other week, y) are not valid either.

MANNER also relates to CAUSE. Again, asking how? does not resolve the ambiguity. Given The legislation itself noted that it [was introduced]x “by request,” [. . . ](wsj0041, 47), we believe the underlined PP indicates the CAUSE and not the MANNER of x because the introduction of the legislation is the effect of the request. Using the extended definition, since request is an event (it implies a change), MNR(by request, y) is discarded based on the domain and range restrictions.

4 Argument Extraction

In order to implement domain and range restrictions, one needs to map words to the four proposed se-mantic classes: situations (si), states (st), qualities (ql) and non temporal abstract objects (ntao). These classes are the ones involved in MNR; work has been done to define in a similar way more relations, but we do not report on that in this paper.

First, the head word of a potential argument is identified. Then, the head is mapped into a semantic class using three sources of information: POS tags, WordNet hypernyms and named entity (NE)types. Table 1 presents the rules that define the map-ping. We obtained them following a data-driven approach using a subset of MANNER annotation from PropBank and FrameNet. Intermediate classes are defined to facilitate legibility; intermediate classes ending in -NE only involve named entity types

Words are automatically POS tagged using a modified Brill tagger. We do not perform word sense disambiguation because in our experiments it did not bring any improvement; all senses are considered for each word. isHypo(x) for a given word w indicates if any of the senses of w is a hyponym of x in WordNet 2.0. An in-house NE recognizer is used to assign NE types. It detects 90 types organized in a hierarchy with an accuracy of 92% and it has been used in a state-of-the-art Question Answering system (Moldovan et al., 2007). As far as the map-ping is concerned, only the following NE types are used: human, organization, country, town, province, other-loc, money, date and time. The mapping also uses an automatically built list of verbs and nouns that encode events (verb_events and noun_events).

The procedure to map words into semantic classes has been evaluated on a subset of PropBank which was not used to define the mapping. First, we selected 1,091 sentences which contained a total of 171 MANNER relations. We syntactically parsed the sentences using Charniak’s parser and then performed argument detection by matching the trees to the syntactic patterns depicted in Section 5. 52,612arguments pairs were detected as potential MANNER. Because of parsing errors, 146 (85.4%) of the171MANNERrelations are in this set.

After mapping and enforcing domain and range constraints, the argument pairs were reduced to11,724 (22.3%). The filtered subset includes 140(81.8%) of the 171 MANNER relations. The filtering does make mistakes, but the massive pruning mainly filters out potential relations that do not hold: it filters 77.7% of argument pairs and it only misclassifies 6 pairs.

5 Lexico-Syntactic Patterns Expressing MANNER

MANNER is expressed by a wide variety of lexico-syntactic patterns, implicitly or explicitly.

Table 2 shows the syntactic distribution of MANNER relation in PropBank. We only consider relations between a single node in the syntactic tree and a verb; MANNER relations expressed by trace chains identifying coreference and split arguments are ignored.

This way, we consider 7,852MANNERoutof the total of the 8,037 PropBank annotates. Because ADVPs and PPs represent 90% of MANNER relations, in this paper we focus exclusively on these two phrases.

For both ADVP and PP the most common direct ancestor is either a VP or S, although examples are found that do not follow this rule. Table 3 shows the number of occurrences for several parent nodes and examples. Only taking into account phrases whose

ancestor is either a VP or S yields a coverage of 98%and thus those are the focus of this work.

5.1 Ambiguities of MANNER

Both ADVPs and PPs are highly ambiguous when the task is to identify their semantics. The PropBank authors (Palmer et al., 2005) report discrepancies between annotators mainly with AT-LOCATION and simply no relation, i.e., when a phrase does not encode a role at all. In their annotation, 22.2% of AD-VPs encode MANNER(30.3% AT-TIME), whereas only 4.6% of PPs starting within and 6.1% starting with at encode MANNER. The vast majority of PPs encode either a AT-TIME or AT-LOCATION.

MANNER relations expressed by ADVPs are easier to detect since the adverb is a clear signal. Adverbs ending in ly are more likely to encode a MANNER. Not surprisingly, the verb they attach to also plays an important role. Section 6.2 depicts the features used.

PPs are more complicated since the preposition per se is not a signal of whether or not the phrase encodes a MANNER. Even prepositions such as under and over can introduce a MANNER. For example, A majority of an NIH-appointed panel recommended late last year that the research continue under carefully controlled conditions, [. . . ] (wsj0047, 9) and[. . . ] bars where Japanese revelers sing over recorded music, [. . . ](wsj0300, 3). Note that in both cases, the head of the NP contained in the PP encoding MANNER(conditions and music) belongs to ntao(Section 4). Other prepositions, like with and like are more likely to encode a MANNER, but again it is not guaranteed.

6 Approach

We propose a supervised learning approach, where instances are positive and negative MANNER examples. Due to their intrinsic difference, we build different models for ADVPs and PPs.

6.1 Building the Corpus

The corpus building procedure is as follows. First, all ADVPs and PPs whose parent node is a VP or S and encode a MANNER according to PropBank are extracted, yielding 3559 and 3499 positive instances respectively. Then, 10,000 examples of ADVPs and another 10,000 of PPs from the Penn TreeBank not encoding a MANNER according to PropBank are added. These negative instances must have as their parent node either VP or S as well and are selected randomly.

The total number of instances, 13,559 for ADVPs and 13,499 for PPs, are then divided into training(60%), held-out (20%) and test (20%). The held-out portion is used to tune the feature set and the final results provided are the ones obtained with the testportion, i.e., instances that have not been used in anyway to learn the models. Because PropBank adds semantic role annotation on top of the Penn TreeBank, we have gold syntactic annotation for all instances.

6.2 Selecting features

Selected features are derived from previous works on detecting semantic roles, namely (Gildea and Jurafsky, 2002) and the participating systems in

CoNLL-2005 Shared Task (Carreras and M`arquez,2005), combined with new, manner-specific features that we introduce. These new features bring a significant improvement and are dependent on the phrase potentially encoding a MANNER. Experimentation has shown that MANNER relations expressed by an ADVP are easier to detect than the ones expressed by a PP.

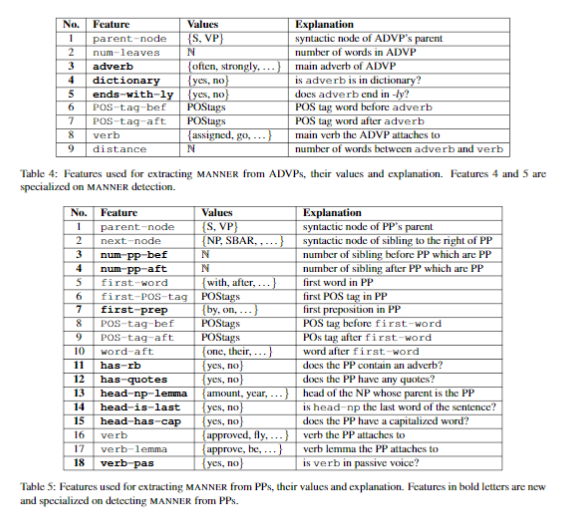

Adverbial Phrases The feature set used is depicted in Table 4. Some features are typical of semantic role labeling, but features adverb, dictionary and ends-with-ly are specialized to MANNER extraction from ADVPs. These three additional features bring a significant improvement (Section 7).

We only provide details for the non-obvious features.

The main adverb and verb are retrieved by selecting the last adverb or verb of a sequence. For example, in more strongly, the main adverb is strongly, and in had been rescued the main verb is rescued

Dictionary tests the presence of the adverb in a custom built dictionary which contains all lemmas for adverbs in WordNet whose gloss matches the regular expression in a .*(manner|way|fashion|style). For example, more.adv.1: used to form the comparative of some adjectives and adverbs does not belong to the dictionary, and strongly.adv.1: with strength or in a strong manner does. This feature is an extension of the dictionary presented in (Girju et al., 2003).

Given the sentence [. . . ] We [work [damn hard] ADVP at what we do for damn little pay]VP, and [. . . ] (wsj1144, 128), the features are: {parent-node: VP, num-leaves: 2, adverb:hard, dictionary:no, ends-with-ly:no, POS-tag-bef:RB, POS-tag-aft:IN, verb:work, distance:1}, and it is a positive instance.

Prepositional Phrases PPs are known to be highly ambiguous and more features need to be added. The complete set is depicted in Table 5.

Some features are typical of semantic role detection; we only provide a justification for the new features added. Num-pp-bef and num-pp-aft captures the number of PP siblings before and after the PP. The relative order of PPs is typically MANNER, AT-LOCATION and AT-TIME (Hawkins, 1999), and this feature captures this idea without requiring temporal or local annotation.

PPs having quotes are more likely to encode a MANNER, the chunk of text between quotes being the manner. For example, use in “very modest amounts” (wsj0003, 10) and reward with “page bonuses” (wsj0012, 8).

head-np indicates the head noun of the NP that attaches to the preposition to form the PP. It is retrieved by selecting the last noun in the NP. Certain nouns are more likely to indicate a MANNER than others. This feature captures the domain restriction. For nouns, only non temporal abstract objects and states can encode a MANNER. Some examples of positive instances are haul in the guests’ [honor], lift in two [stages], win at any [cost], plunge against the [mark] and ease with little [fanfare]. However, counterexamples can be found as well: say through his [spokesman] and do over the [counter].

Verb-pas indicates if a verb is in passive voice. In that case, a PP starting with by is much more likely to encode an AGENT than a MANNER. For example, compare (1) “When the fruit is ripe, it [falls]y from the tree [by itself]PP,” he says. (wsj0300, 23); and (2)Four of the planes [were purchased]y [by International Lease]PP from Singapore Airlines in a [. . . ] transaction (wsj0243, 3).In the first example a MANNER holds; in the second an agent.

Given the sentence Kalipharma is a New Jersey-based pharmaceuticals concern that [sells products[under the Purepac label]PP]VP. (wsj0023, 1), the features are: {parent-node:VP, next-node:-, num-pp-bef:0, num-pp-aft:0, first-word:under, first-POS-tag:IN, first-prep:under, POS-tag-bef:NNS, POS-tag-aft:DT, word-aft:the, has-rb:no, has-quotes:no, head-np-lemma:label, head-is-last:yes, head-has-cap:yes, verb:sells, verb-lemma:sell, verb-pas:no},and it is a positive instance.

7 Learning Algorithm and Results

7.1 Experimental Results

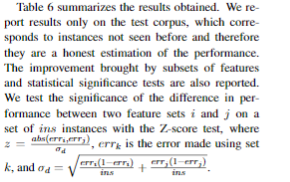

As a learning algorithm we use a Naive Bayes classifier, well known for its simplicity and yet good performance. We trained our models with the training corpus using 10-fold cross validation, and used the held-out portion to tune the feature set and adjust parameters. More features than the ones depicted were tried, but we only report the final set. For example, named entity recognition and flags indicating the presence of AT-LOCATION and AT-TIME relations for the verb were tried, but they did not bring any significant improvement.

ADVPs The full set of features yields a F-measure of 0.815. The three specialized features (3, 4 and5) are responsible for an improvement of .168 in the F-measure. This difference in performance yields a Z-score of 7.1, which indicates that it is statistically significant.

PPs All the features proposed yield a F-measure of0.693. The novel features specialized in MANNER detection from PPs (in bold letters in Table 5) bring an improvement of 0.059, which again is significant.

The Z-score is 2.35, i.e., the difference in performance is statistically significant with a confidence greater than 97.5%. Thus, adding the specialized features is justified.

7.3 Error Analysis

The mapping of words to semantic classes is data-driven and decisions were taken so that the overall accuracy is high. However, mistakes are made. Given We want to [see]y the market from the inside, he underlined PP encodes a MANNER and the mapping proposed (Table 1) does not map inside to ntao. Similarly, given Like their cohorts in political consulting, the litigation advisers [encourage]y their clients [. . . ], the underlined text encodes a MANNER and yet cohorts is subsumed bysocialgroup.n.1and therefore is not mapped to ntao.

The model proposed for MANNER detection makes mistakes as well. For ADVPs, if the main adverb has not been seen during training, chances of detecting MANNER are low. For example, the classifier fails to detect the following MANNER relations: [. . . ] which together own about [. . . ](wsj0671, 1); and who has ardently supported [. . . ](wsj1017,26) even though ardently is present in the dictionary and ends in -ly;

For PPs, some errors are due to the PropBank annotation. For example, in Shearson Lehman Hutton began its coverage of the company with favorable ratings. (wsj2061, 57), the underlined text is annotated asARG2, even though it does encode a MANNER. Our model correctly detects a MANNER but it is counted as a mistake. Manners encoded by under and at are rarely detected, as in that have been consolidated in federal court under U.S. District Judge Milton Pollack(wsj1022.mrg, 10).

8 Comparison with Previous Work

To the best of our knowledge, there have not been much efforts to detect MANNER alone. Girju et al.(2003), present a supervised approach for ADVP similar to the one reported in this paper, yielding a F-measure of .665. Our augmented feature set obtains a F-measure of .815, clearly outperforming their method (Z-test, confidence>97.5%). Moreover, ADVPs only represent 45.3% of MANNER as asemantic role in PropBank. We also have presented a model to detect MANNER encoded by a PP, the other big chunk of MANNER(44.6%) in PropBank.

Complete systems for Semantic Role Labeling perform poorly when detecting MANNER; the Top-10 systems in CoNLL-2005 shared task3obtainedF-measures ranging from .527 to .592. We have trained our models using the training data provided by the task organizers (using the Charniak parser syntactic information), and tested with the provided test set (test.wsj). Our models yield a Precision of.759 and Recall of .626 (F-measure .686), bringing a significant improvement over those systems (Z-test, confidence>97.5%). When calculating recall, we take into account all MANNER in the test set, not only ADVPs and PPs whose fathers are S or VP (i.e. not only the ones our models are able to detect). This evaluation is done with exactly the same data pro-vided from the task organizers for both training and test.

Unlike typical semantic role labelers, our features do not include rich syntactic information (e.g. syntactic path from verb to the argument). Instead, we only require the value of the parent and in the case of PPs, the sibling node. When repeating the CoNLL-2005 Shared Task training and test using gold syntactic information, the F-measure obtained is .714, very close to the .686 obtained with Charniak syntactic trees (not significant, confidence>97.5%).

Even though syntactic parsers achieve a good performance, they make mistakes and the less our models rely on them, the better.

9 Composing MANNER with PURPOSE

MANNER can combine with other semantic relations in order to reveal implicit relations that otherwise would be missed. The basic idea is to compose MANNER with other relations in order to infer another MANNER. A necessary condition for combining MANNER with another relation R is the compatibility of RANGE(MNR) with DOMAIN(R) or RANGE(R) with DOMAIN(MNR). The extended definition (Section 3) allows to quickly determine if two relations are compatible (Blanco et al., 2010).

The new MANNER is automatically inferred by humans when reading, but computers need an explicit representation. Consider the following example: [ . . . ]the traders [place]y orders[via computers]MNR [to buy the basket of stocks. . . ]PRP (wsj0118, 48). PropBank states the basic annotation between brackets: via computers is the MANNER and to buy the basket [. . . ] the PURPOSE of the place orders event. We propose to combine these two relations in order to come up with the new relation MNR(via computers, buy the basket [. . . ]).This relation is obvious when reading the sentence, so it is omitted by the writer. However, any semantic representation of text needs as much semantics as possible explicitly stated.

This claim is supported by several PropBank examples: (1)The classics have [zoomed]y [in price]MNR [to meet the competition]PRP, and . . (wsj0071, 9) and (2). . . the government [curtailed]y production [with land-idling programs]MNR [to reduce price-depressing surpluses]PRP (wsj0113, 12). In both examples, PropBank encodes the MANNER and PURPOSE for event y indicated with brackets. After combining both relations, two new MANNER arise: MNR(in price,meet the competition) and MNR(with land-idling programs, reduce price-depressing surpluses)

Out of 237 verbs having in PropBank both PURPOSE and MANNER annotation, the above inference method yields 189 new valid MANNER not present in PropBank (Accuracy .797).

MANNER and other relations. MANNER does not combine with relations such as CAUSE, AT-LOCATION or AT-TIME. For example, given And they continue [anonymously]x,MNR[attacking]y CIA Director William Webster [for being too accommodating to the committee]z, CAU (wsj0590, 27), there is no relation between x and z. Similarly, given [In the tower]x, LOC, five men and women [pull]y [rhythmically]z, MNR on ropes attached to [. . . ] (wsj0089, 5) and [In May]x, TMP, the two companies, [through their jointly owned holding company]z, MNR, Temple, [offered]y[. . . ](wsj0063,3), no connection exists between x and z.

10 Conclusions

We have presented a supervised method for the automatic discovery of MANNER. Our approach is simple and outperforms previous work. Our models specialize in detecting the most common pattern encoding MANNER. By doing so we are able to specialize our feature sets and outperform previous approaches that followed the idea of using dozens of features, most of them potentially useless, and letting a complicated machine learning algorithm decide the actual useful features.

We believe that each relation or role has its own unique characteristics and capturing them improves performance. We have shown this fact for MANNER by examining examples, considering the kind of arguments that can be part of the domain and range, and considering theoretical works (Hawkins, 1999).

We have shown performance using both gold syntactic trees and the output from the Charniak parser, and there is not a big performance drop. This is mainly due to the fact that we do not use deep syntactic information in our feature sets.

The combination of MANNER and PURPOSE opens up a novel paradigm to perform semantic inference. We envision a layer of semantics using a small set of basic semantic relations and inference mechanisms on top of them to obtain more semantics on demand. Combining semantic relations in order to obtain more relation is only one of the possible inference methods.

References

Collin F. Baker, Charles J. Fillmore, and John B. Lowe.1998. The Berkeley FrameNet Project. In Proceedings of the 17th international conference on Computational Linguistics, Montreal, Canada.

Eduardo Blanco, Hakki C. Cankaya, and Dan Moldovan.2010. Composition of Semantic Relations: Model and Applications. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Computational Linguistics (COLING2010), Beijing, China.

Xavier Carreras and Luıs Marquez. 2005. Introduction to the CoNLL-2005 shared task: semantic role labeling. In CONLL ’05: Proceedings of the Ninth Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning, pages 152–164, Morristown, NJ, USA.

Du S. Chang and Key S. Choi.2006. Incremental cue phrase learning and bootstrapping method for causality extraction using cue phrase and word pair probabilities. Information Processing & Management, 42(3):662–678.

Dmitry Davidov and Ari Rappoport. 2008. Unsupervised Discovery of Generic Relationships Using Pattern Clusters and its Evaluation by Automatically Generated SAT Analogy Questions. In Proceedings ofACL-08: HLT, pages 692–700, Columbus, Ohio.

Dmitry Davidov, Ari Rappoport, and Moshe Koppel.2007. Fully Unsupervised Discovery of Concept-Specific Relationships by Web Mining. In Proceedings of the 45th Annual Meeting of the Association of Computational Linguistics, pages 232–239, Prague, Czech Republic.

Daniel Gildea and Daniel Jurafsky. 2002. Automatic Labeling Of Semantic Roles. Computational Linguistics, 28:245–288.

Roxana Girju, Manju Putcha, and Dan Moldovan. 2003.Discovery of Manner Relations and Their Applicability to Question Answering. In Proceedings of the ACL2003 Workshop on Multilingual Summarization and Question Answering, pages 54–60, Sapporo, Japan.

Roxana Girju, Adriana Badulescu, and Dan Moldovan.2006. Automatic Discovery of Part-Whole Relations. Computational Linguistics, 32(1):83–135.

Roxana Girju, Preslav Nakov, Vivi Nastase, Stan Szpakowicz, Peter Turney, and Deniz Yuret.2007.SemEval-2007 Task 04: Classification of Semantic Relations between Nominals. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Workshop on Semantic Evaluations (SemEval-2007), pages 13–18, Prague, Czech Republic.

Ana M. Giuglea and Alessandro Moschitti. 2006. Semantic role labeling via FrameNet, VerbNet and Prop-Bank. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Computational Linguistics and the 44th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 929–936, Morristown, NJ, USA.

John A. Hawkins. 1999. The relative order of prepositional phrases in English: Going beyond Manner-Place-Time. Language Variation and Change, 11 (03):231–266.

Marti A. Hearst. 1992. Automatic Acquisition of Hyponyms from Large Text Corpora. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, pages 539–545.

Hermann Helbig. 2005. Knowledge Representation and the Semantics of Natural Language. Springer.

Toru Hirano, Yoshihiro Matsuo, and Genichiro Kikui.2007. Detecting Semantic Relations between Named Entities in Text Using Contextual Features. In Proceedings of the 45th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Demo and Poster Sessions, pages 157–160, Prague, Czech Republic.

Luis Marquez, Xavier Carreras, Kenneth C. Litkowski, and Suzanne Stevenson. 2008. Semantic Role Labeling: An Introduction to the Special Issue. Computational Linguistics, 34(2):145–159.

Dan Moldovan, Christine Clark, and Mitchell Bowden.2007. Lymba’s PowerAnswer 4 in TREC 2007. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth Text REtrieval Confer-ence (TREC 2007).

Paul Nulty.2007.Semantic Classification of Noun Phrases Using Web Counts and Learning Algorithms. In Proceedings of the ACL 2007 Student Research Workshop, pages 79–84, Prague, Czech Republic.

Martha Palmer, Daniel Gildea, and Paul Kingsbury.2005.The Proposition Bank: An Annotated Corpus of Semantic Roles. Computational Linguistics, 31(1):71–106.

Vivek Srikumar, Roi Reichart, Mark Sammons, Ari Rappoport, and Dan Roth. 2008. Extraction of Entailed Semantic Relations Through Syntax-Based Comma Resolution. In Proceedings of ACL-08: HLT, pages1030–1038, Columbus, Ohio.

Barker Szpakowicz, Ken Barker, and Stan Szpakowicz.1995. Interactive semantic analysis of Clause-Level Relationships. In Proceedings of the Second Conference of the Pacific Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 22–30.

Marta Tatu. 2005. Automatic Discovery of Intentions inText and its Application to Question Answering. In Proceedings of the ACL Student Research Workshop, pages 31–36, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Peter D. Turney. 2006. Expressing Implicit Semantic Relations without Supervision. In Proceedings of the21st International Conference on Computational Linguistics and 44th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 313–320, Sydney, Australia.